When I took up fishing again after a 50 year hiatus, my wife Gray was bewildered: “Phil, you’ve spent your whole career being nice to fish. Why do you suddenly want to be mean to them?”

I could say I went fishing for the spectacular sunrises and experience of nature, but Gray would quickly note that I could get up at 3:30 am to be on Florida Bay for the sunrise, spend the morning watching shorebirds, manatees, dolphins, rays, and sharks, and come home to enjoy lunch and a nap, all while leaving the fish in peace.

So hers is a fair question. I studied electric fish and mosquitofish for 35 years at Cornell and FIU. I had a massive fish-rearing facility on the roof of my building where our fish bred because we made them so happy. An undercover plant from PETA worked as a technician in my lab for a few months then left because he couldn’t find any evidence that we were inhumane in our treatment of fish. I definitely don’t want to be mean to fish.

So, yes, my love of fishing embodies a patent contradiction in my values. I truly love all the wild things and trying to catch fish. I especially enjoy chasing fish with a fly rod, widely recognized as the least efficient way to actually catch a fish.

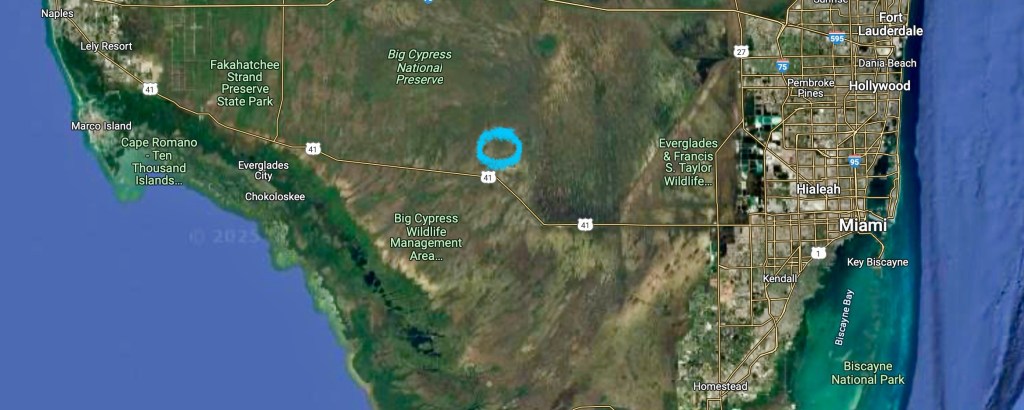

With that bed of nettles as our background, let’s relocate temporarily to the site of the sunrise photo, a seagrass flat in Florida Bay, two miles south of the Flamingo Marina in Everglades National Park. In a future essay, I’ll tell you all the reasons you should NOT fish there, but this day I will share some of its magic.

Here’s the flat surrounding a mangrove key a few minutes after sunrise. This light always enchants me. Look for a moment and you’ll see the water is pink dimpled with dark blue, far prettier to my eye than Christo’s famous pink island wrapping.

The water surface reflects the sky at low sun angles so my iPhone camera can’t see into the water to document for you how the fish are going about their morning activities. That would require a circular polarizer on my iPhone (wait, look it up… PolarPro makes a good one). But I’m up on the poling platform of my skiff this morning wearing polarized sunglasses. You’ll have to trust me when I tell you what fish I’m seeing and what they are doing.

Mullet are flipping and splooshing in the shallows, while egrets line up to try for the small ones. From the key comes the hollow whinny of a Bald Eagle, the raucous clatter of a Mangrove Clapper Rail, and the sweet song of a Yellow Warbler. Against the key lies a deeper channel where I spot a nice redfish but I won’t try for it. A five foot lemon shark cruises the channel, not far behind. Hooking a snook or redfish in any channel at Flamingo is tantamount to feeding a shark. I do not feed sharks or alligators, for similar reasons.

Two juvenile Goliath Groupers, about 18” long, are out in the open on the flat. Young Goliaths normally spend their days holed up in the mangroves, roving the flat at night. But here they are in the light of day.I watch to see what these young groupers will do when they’re caught out in their pj’s with a flats skiff poling towards them. When I get closer, they panic and swim to the nearest clump of red mangroves, sticking their heads in the roots and leaving their mottled brown and black bodies sticking out in the open. With their heads concealed, they can’t see me, so I guess I’m not supposed to see them either, but they look thoroughly silly.

Two young redfish with light gold bodies and blue tails are cruising the shoreline. I pitch a sparkly spoon fly in front of them, then retrieve it. One redfish starts to follow the fly, then changes its mind and wanders back to cruise with its friend. A different fly might have worked better, but which one? Unlike a rising trout that feeds for a while in one spot while the flyfisher tries one fly after another, a flats fish on the move rarely affords a second chance.

The edge of the flat becomes a reverse shower of small jacks taking to the air. Underneath the water, I presume, a school of large jacks roars through the water in hot pursuit. In fifteen seconds, the water is still once again. It’s a fish-eat-fish world on the flats.

I round the corner of the key and the glassy water surface erupts and goes still in alternation. Silver tails appear briefly and disappear. A school of juvenile tarpon is actively feeding on baitfish.

The prey this morning is a school of anxious young mangrove snappers that’s holding in one area. To my happy surprise, the tarpon are cruising back and forth to take multiple shots at the bait school and affording me a parallel opportunity with my fly rod.

I throw a black tarpon fly in front of the advancing tarpon with no success. The same fly worked last week in murky water four miles to the east, but the water here today is clear. Oh, right. Light-colored flies work better in clear water than dark patterns because fish (including baitfish) in clear water change to lighter, more reflective body colors for better camouflage. I knew that. The tarpon will be coming back soon for another pass at the snappers, so I remove the black fly and select a big gray & white snook fly that I tied but never put in front of a fish. If I stretch my imagination, this fly could resemble a young mangrove snapper. It looks very fishy in the water and it’s not black.

I attach this snook fly to the heavy tarpon-proof bite tippet on my leader, and cast it in front of the tarpon school. To complete the illusion of a small fish finding itself in the wrong place at the wrong time, I make the fly attempt an escape. It works. One of the larger tarpon breaks from the school and grabs the hapless fly. I set the hook, but the tarpon doesn’t seem to care. The lining of a tarpon’s mouth is as tough as Kevlar – I’ve seen a tarpon consume a whole blue crab without chewing. But, feeling the line resistance, the tarpon forcibly yanks some fly line from my left hand and swims back into formation in the school. I restore tension on the line, putting a good arc into the 7-weight fly rod. The tarpon resists for a moment, then jumps clear of the water, snapping its body back and forth in the air and creating the slack needed to neatly toss my fly.

You normally drop the rod tip when a tarpon jumps, precisely to keep it from creating that line slack, but I kept light tension on specifically to help the tarpon escape. More on that in a moment.

Free of the leader’s encumbrance, the young tarpon, roughly 10 pounds’ worth, once again resumes its position in the school as the members continue their search for yummy little mangrove snappers.

* * *

Even though a fish’s face doesn’t change with mood, I swear this tarpon glared with an annoyed expression in its whole body. Perhaps it was in the way it shouldered loose some free line and went back to what it was doing before. It was never so clear that my hard earned fly-fishing skills, such as they are, do indeed annoy the fish.

When a woman sends me a message like this, it stings. Same with a fish it turns out. I didn’t spend 35 years studying fish behavior to no effect.

Increasingly, I compromise, seeking a bite on the fly then a self-release at a distance.

When a fish takes a fly that I tied myself, I delight at having completed the illusion. My heart skips a beat at the sudden appearance of weight and power on the other end of the fly line gripped in my left hand. If I’m lucky, the fish makes a fast initial run, and maybe, if it’s the right species, it makes a couple of spectacular jumps. If it’s a new species for me, I want to see it up close and take a photo to remember it better. But for familiar species I do what I can to help the fish pitch the fly and get on with its fish life, ideally without my having to net and unhook it.

We’ll see how that deal sits with me. And, I suppose, with the fish.

© Philip Stoddard