As I went walking I saw a sign there,

And on the sign it said “No Trespassing.”

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing.

That side was made for you and me.

© Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc.

& TRO-Ludlow Music, Inc. (BMI)

Contrary to my religious practice, I have been off the water for two long weeks. Bunch of pressing things going on, but my psyche demands TOW (time on water). Rain is predicted for Saturday afternoon but the morning looks good in the western Everglades if I stay south of the fire. The plan unfolds to shirk the day’s assorted social obligations and to start the morning fly fishing for juvenile tarpon from my kayak. Play it by ear after that.

I packed the car the night before, bringing a single 7-weight fly rod, a clear-tip intermediate sink-tip line, and an assortment of proven flies that I tied to entice juvenile tarpon. Going “fly or die”.

* * *

FINDING JUVENILE TARPON AFTER A COLD SNAP

A few days back, a friend reported seeing 100 dead juvenile tarpon in my favorite Everglades tarpon fishing area, killed by the recent cold event. The spot I chose for today, ~60 miles northwest of there, is a brackish canal network dug 20’ deep to excavate fill to create adjacent dry land for buildings. Some people still think building in the Everglades is a good idea. On the plus side, deep water makes a good thermal refuge for manatees and juvenile tarpon during a winter cold snap. I always find tarpon holed up there in the winter and especially when it’s cold.

The general area sees significant fishing pressure, evidenced by the occasional snagged fishing lure I pluck from a mangrove and by the landing net sitting next to a kayak on the shore at a nearby residence. Educated tarpon are hard to catch, especially on fly, and these tarpon most often refuse my two best producers along the Tamiami Trail: Mike Connor’s Glades Minnow and Jay Levine’s black micro-bunny.

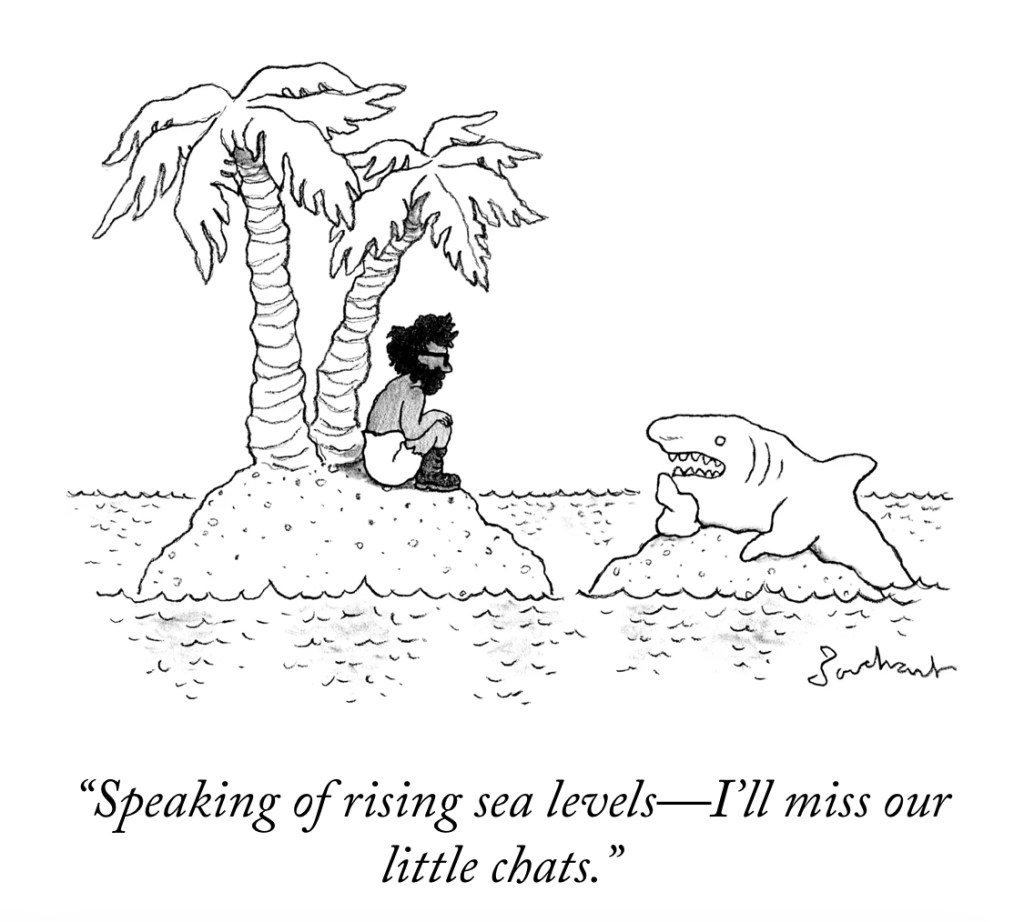

Water access is controversial. There’s a boat launch a mile away, but a clear “NO TRESPASSING” sign is posted on a buoy you’d have to pass to get to the canal network. It’s all public water but I assume someone of authority doesn’t want motor boats shattering the peace in the canal area. Fishermen have told me about being issued a $125 fine plus administrative fees when they were caught on the wrong side of that sign by an officer from the Florida Wildlife Commission.

Florida Statutes Ch 810.011 states that No Trespassing signs must be “…placed conspicuously at all places where entry to the property is normally expected or known to occur.”

If I approach the canal system in a kayak from the tidal creek on other side, the only posted sign says not to feed the alligators. By my read of the statute and the signage, a person can lawfully enter by kayak or canoe from this creek (nix the paddleboard – see below). To honor the implied intent, I paddle solo and fish in silence.

While no sign prohibits entry from the creek, a militia of large alligators guards a shallow area in the creek outflow. It’s such a good spot to snap up a passing fish that only the biggest gators can command a seat at the table. They allowed me to pass hassle-free on prior trips, but I always treat them with respect and get past them quickly lest they think up some excuse to engage.

* * *

THE WEE HOURS

Dream after dream has me looking for a bathroom. At 1:35 am, my conscious brain integrates the repeated hints that I need to get up to pee. Sleep is over. The alarm is set for 3:30 am, but lying awake at 3:05 I give up and start my day. Dress, shave, sunscreen, pet the cat, coffee, granola, Heather Cox Richardson, pack the cooler, and hit the road to cross the Tamiami Trail in the dark.

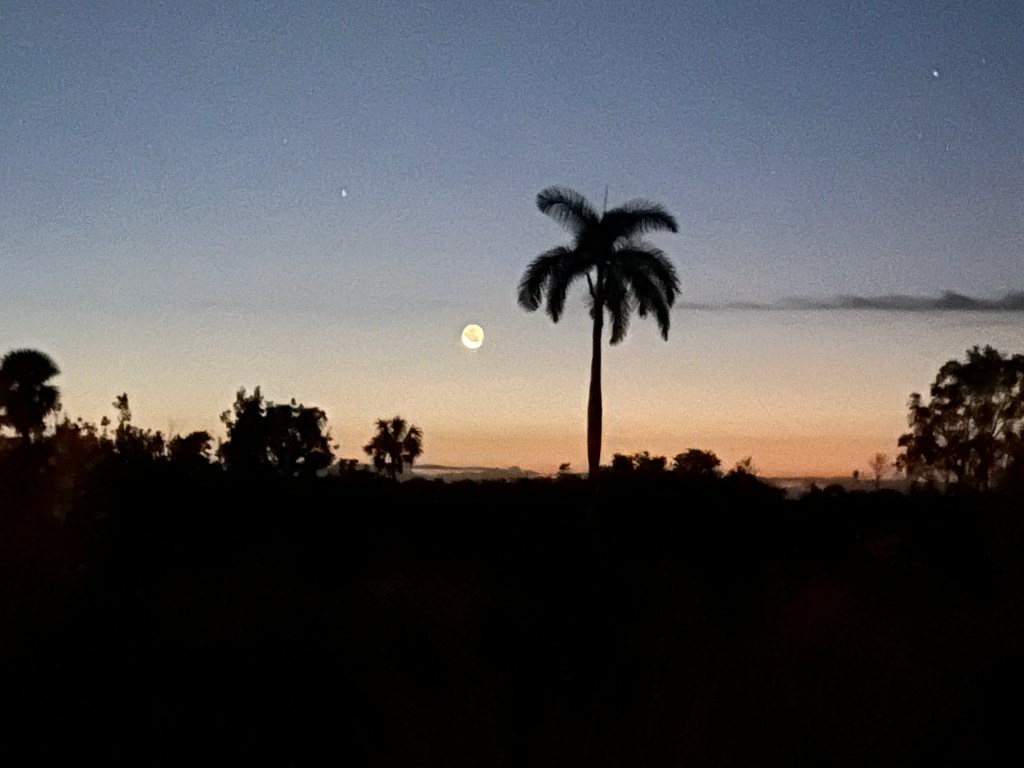

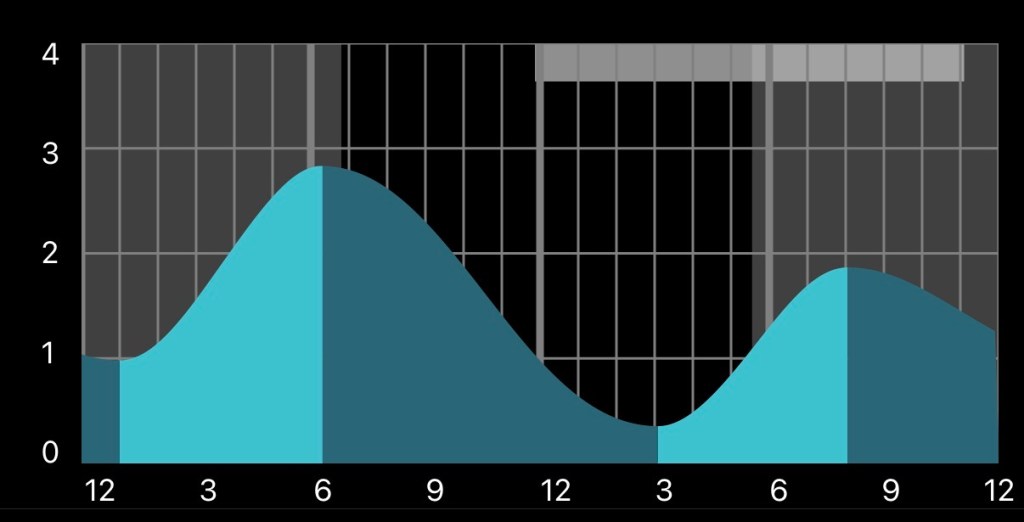

A dense fog in the Everglades blocks the full moon and lowers my driving speed to 35 mph. Ninety minutes later, I pull off onto a gravel lot in pitch dark. Fifty minutes to sunrise, and twenty to the start of civil twilight.

* * *

GATOR GAUNTLET

Water levels are very low this winter. The gators’ usual ambush spot in the shallow portion of the creek bed is high and dry. Seeing no gator eyes glowing in the beam of my headlamp, I haul my kayak overland in the dark to the rocky exposed creek bed. The sky shows the very first hint of dawn as I launch in the fog.

The dark water explodes around my kayak. The gators hadn’t gone far. Huge bodies, black and cream, churn in front of me and on either side. So much for silence.

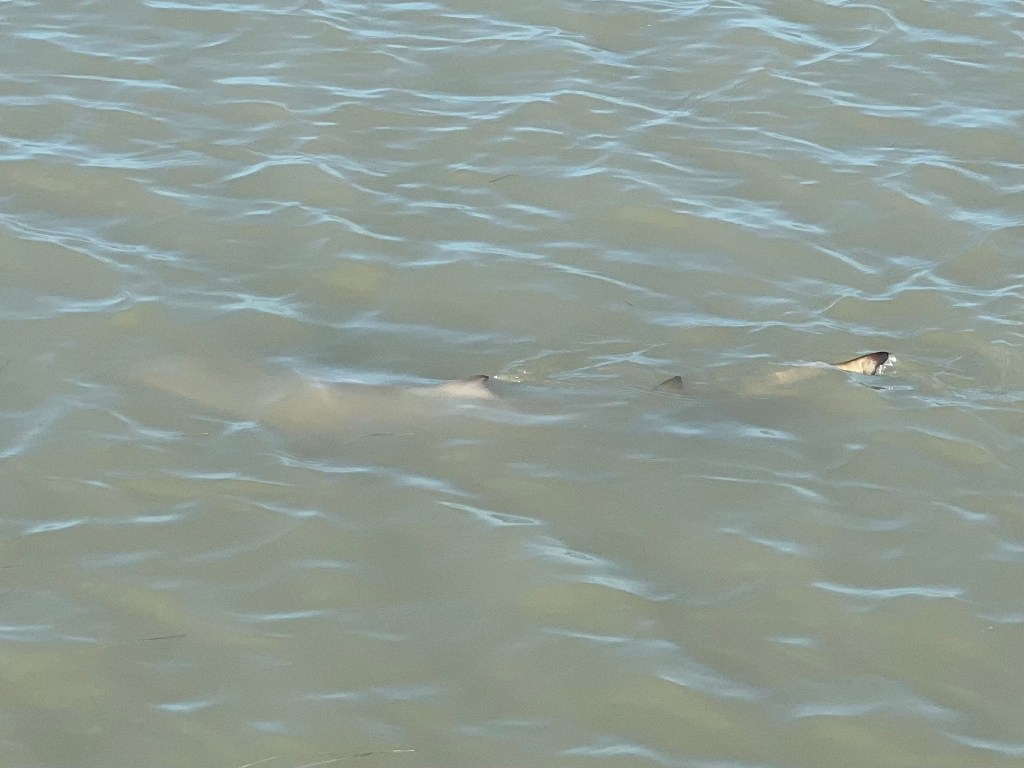

The glassy water is dotted with dead cichlids killed by the cold, mostly tilapia. I’m sure the gators have been enjoying the feast. Just past the gators, foot-long mullet begin leaping into the air and crashing onto their sides. Nobody knows why mullet jump, but I’m pretty confident it’s a courtship display. Fifty yards further, a dorsal fin and tail nick the surface. Tarpon can breathe air and come up to the surface for a quick gulp in a behavior known as “rolling”. The tarpon are alive and rolling.

* * *

FLIES

In very tannic or murky water, tarpon bite dark-colored flies, but they prefer white flies in clear water. The water today is clear but somewhat tannic, so it’s anybody’s guess what shade of fly will do best. I start with a black baitfish fly that’s been super-effective for tarpon and snook in dark water.

I pull some fly line off the reel and make my first cast in front of three rolling tarpon. Nice to have my right arm working again after four months of physical therapy for a torn muscle in my rotator cuff.

The tarpon ignore this black fly over the next dozen casts. That means they won’t take Jay’s black micro-bunny either. I switch to a white micro-bunny fly. They like that one better, but not enough. They nip and pull its tail, “short-strikes” in fly fishing parlance. I begin counting short strikes.

Since they don’t want black or white, how about olive? I try an olive micro-bunny. Nothing. Black & white bunny? Nope. White baitfish with swishy peacock herl tail? Nope. Black & purple tie of Paul Nocifora’s BMF? It gets a bunch more short strikes, but no eats, even after I snipped off the weed guard. A black & purple tie of Chico Fernandez’s Marabou Madness, weighted to get down deeper? Nope.

I have been on the water for two hours now, fishing the best time of the day. I have made over a hundred casts at rolling tarpon with seven flies, two of which received 13 short strikes between them but zero eats. Mangroves lining the canals have been more eager than the tarpon, grabbing my flies on the errant backcasts. My newly rehabilitated rotator cuff is starting to complain.

I suppose it’s possible the tarpon, though plentiful, just won’t bite today. The water feels coolish but not cold, maybe 68°.

Not catching fish is hardly the worst thing on a spring morning in the mangroves. A bull manatee is swimming back and forth underneath me, probably curious about my kayak. Chortling songs of Purple Martins grace the air. Mullet sploosh nonstop under the watch of Great Blue Herons waiting in ambush on the odd bit of open shoreline. Anhingas and cormorants dry in the trees overhead as they digest their breakfasts. Alligators rise and sink as I pedal-paddle past.

* * *

THE DEVIL’S DAUGHTER

Master fly designer Drew Chicone of Ft. Myers publishes an email newsletter with detailed instructions for tying his more successful fly designs.

Drew invented “The Devil’s Daughter”, a big black fly for targeting overfished snook and juvenile tarpon who have seen every fly in the box. It’s a complicated tie as saltwater flies go, combining shimmering peacock herl, swishy ostrich herl, and fluffy marabou feathers into a pulsating body, with a head of spun black deer hair that displaces water as the fly moves. It’s light for its size, lands softly, wets quickly, swishes enticingly, and pushes water to announce its passage. I had tied one and used it only once, but it caught a 40 pound canal tarpon.

This fly is in my collection today so I throw it in front of the rolling tarpon and move it through the water steadily with tiny twitches to make it quiver. The fly stops and I give the line a tug…

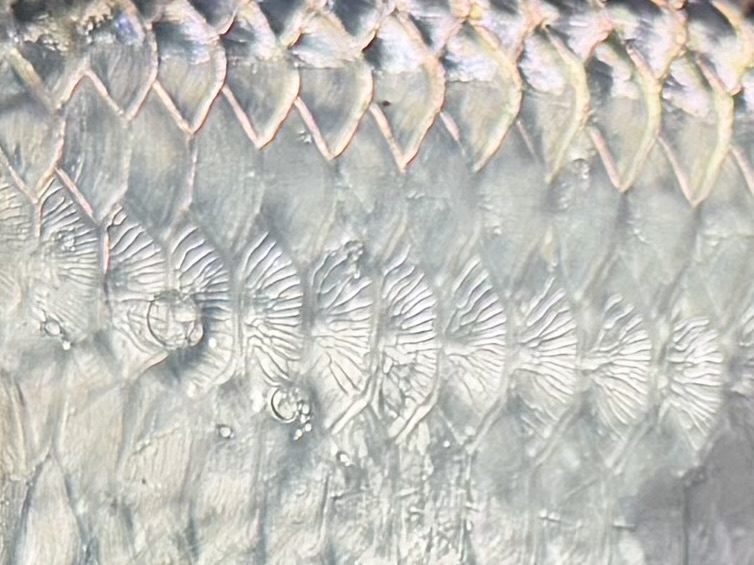

Line rips out of my hand and screams off the reel. I take back line and a five pound tarpon goes airborne. They always do and it’s always a remarkable show of athleticism.

Over the next two hours I catch and release eight tarpon ranging from 3 to 10 pounds. Two toss the fly and six have to be unhooked in the net.

Expert wisdom has it that the fly design matters much less than how you move it. True enough, but this morning’s fishing success has hinged on one black fly designed by Drew Chicone. Both times I’ve fished it, 1/3 of tarpon contacts resulted in hook-ups. Heck of a fly, Drew.

* * *

The sky opens up as I pull into the driveway. I could use a nap.

One last nod to the enduring spirit of Woody Guthrie:

Roll on sweet tarpon, roll on.

© Philip Stoddard